How to Get Sh*t Done in Washington DC

8 steps for think tanks to turn an idea into policy change

We all know that Washington is broken. People complain that it’s impossible to get stuff done. But then, actually quite often, stuff does get done. And sometimes, just sometimes, things happen because people outside government come together to push a new idea inside government.

I was thinking about this a lot when, on June 11, the World Bank announced an end to its ban on nuclear. The Energy for Growth Hub played a part in the Bank’s policy shift as part of a persistent and determined coalition of other think tanks, Hill staff and insiders. Why were we successful? It came down to eight steps.

Hopefully other think tanks, especially those struggling to make policy impact, glean something from this experience.

First: What are think tanks not for?

Andrew Selee has a lovely little book What Should Think Tanks Do? And Tevi Troy has a terrific essay, Devaluing the Think Tank, that I think about often, especially because Troy chronicles how some conservative organizations have been influential by patiently staying on message for decades.

Let me start by revealing my strong bias that think tanks should not exist to write academic reports no one reads. Or host meetings for egos’ sake. Or serve as a gentle pasture for retired ‘formers.’

Everything a think tank does should have a purpose. IMO, think tanks should exist for one thing and one thing only: to get policy change done.

I learned a mountain of lessons from Nancy Birdsall who built the Center for Global Development from scratch. She insisted that everyone on her team share a passion for ending global poverty, but encouraged radical experimentation of how to get there. (In an early sign of embracing apostasy, her very first big hire was Bill Easterly who had just been thrown out of the World Bank.) From Bill I learned that, if you think the status quo sucks, challenging orthodoxy is extremely useful. I’ve drawn lots of other lessons from working in some capacity in at least six other think tanks over my career, each with a niche, some focused on concrete action more than others.

When I created the Energy for Growth Hub, I tried to take this just-get-sh*t-done approach to the extreme. By design, we host almost no events and rarely attend conferences, except when the purpose is dead clear. We don’t publish long glossy reports. We’ve never held a gala. Our model is to stay in the policy trenches, largely out of sight, and be a trusted source of reliable analysis and new ideas. Our work is tailored to our micro-targeted policymaker audience, so everything written strives to be as short and jargon-free as possible.* We fail at this often (!), but we are always aspiring for brevity and clarity because that’s how to get stuff done.

*Side note for a tale that may or may not be true but has stuck with me: When Henry Kissinger was in the White House, he rejected a new staffer’s memo immediately as too long and too unclear. He rejected the next version, and the next, and the next. When the exhausted staffer finally said to him, “Sir, this is as short and clear as I can write it,” Kissinger replied, “Good. Now I’ll read it.”

So, how do think tanks make policy change happen?

Back in 2020, I wrote about the creation of the US Development Finance Corporation, which began as scrawl on Ben Leo’s napkin and is now a (soon-to-be $250 billion) federal agency at the vanguard of US foreign policy. That kind of Blue-Sky-Idea-to-Reality is rare. More often, think tanks have impact when they push for small incremental changes that can have a ripple effect, like a rule change or altering a metric or even just a neutral third party pitching a simple idea that could not be proposed by negotiators themselves.

The June 11 lifting of the World Bank’s ban on nuclear was another significant policy change where outside groups, including mine, played pivotal roles. At a recent retreat of the Hub’s board and staff, we reflected on how it happened and what lessons we might learn for other ideas we’d like to see happen, like adoption of the Modern Energy Minimum or a new global norm for power contract transparency or the launch of Energy Security Compacts.

This is far more art than science, but having a strong narrative is central to every success. Stories can convey our approach. More importantly, stories are how we learn. All stories are different. The players, the context, the climax. But they all share a common arc.

Which takes me back to the World Bank nuclear story. To explain what happened (at least from my narrow perspective) and draw lessons, here are 8 steps that describe that common arc, that story of an idea to policy change:

1. EXPLORE to find a solvable problem

Think tanks have to be on the hunt for big problems that are holding back progress. In the World Bank nuclear case, countries like Ghana were getting lots of advice from the Bank on everything from debt to infrastructure planning. But Ghana’s aspiration for a nuclear reactor to replace their gas in the mid 2030s was taboo because the World Bank had a policy to not talk about nuclear power or allow nuclear expertise to germinate inside the building (see fn 2 on page 14). Worse, the Bank’s private sector IFC put nuclear on its list of banned investments, alongside weapons and whiskey. This seemed like a problem for Ghana and other countries that might want to consider nuclear power. It also wasn’t very helpful for US nuclear developers who might want to one day export to emerging markets and would benefit from a fair playing field. So, we thought we might have found a problem to take to the next step.

2. DIG into the data

Evidence helps you figure out the extent of the problem, whether it's worth tackling, and to eventually make your case why a change may be needed. Back in 2020, we created a system to assess whether countries were taking concrete steps (not just issuing press releases) to get ready for nuclear power. The data and the first map showed very clearly that Ghana was not alone. Lots of countries who borrow from the World Bank are also serious about nuclear power. The demand was clear.

3. TEST your arguments.

I'm an introvert so this one is hard, but we have to get out there and, er, talk to people. It’s not just about being right or having a bright idea. We have to get reactions and see what sticks. We have to iterate. Did others think the Bank nuclear policy was actually a problem? (Some said yes, others no.) Why did they care? (Some wanted more energy for their countries, others wanted to box out the Russians and Chinese.) Which arguments resonated? (Poverty and climate, mostly no. Jobs and geostrategic competition, absolutely yes.) This input, over multiple years, helped our effort evolve.

4. DIVE into political tactics.

I dislike the term “theory of change,” but tactics are where we reveal our gameplan and our assumptions. Here is where we identify who we think matters, what they really care about, and who influences them most. We need to:

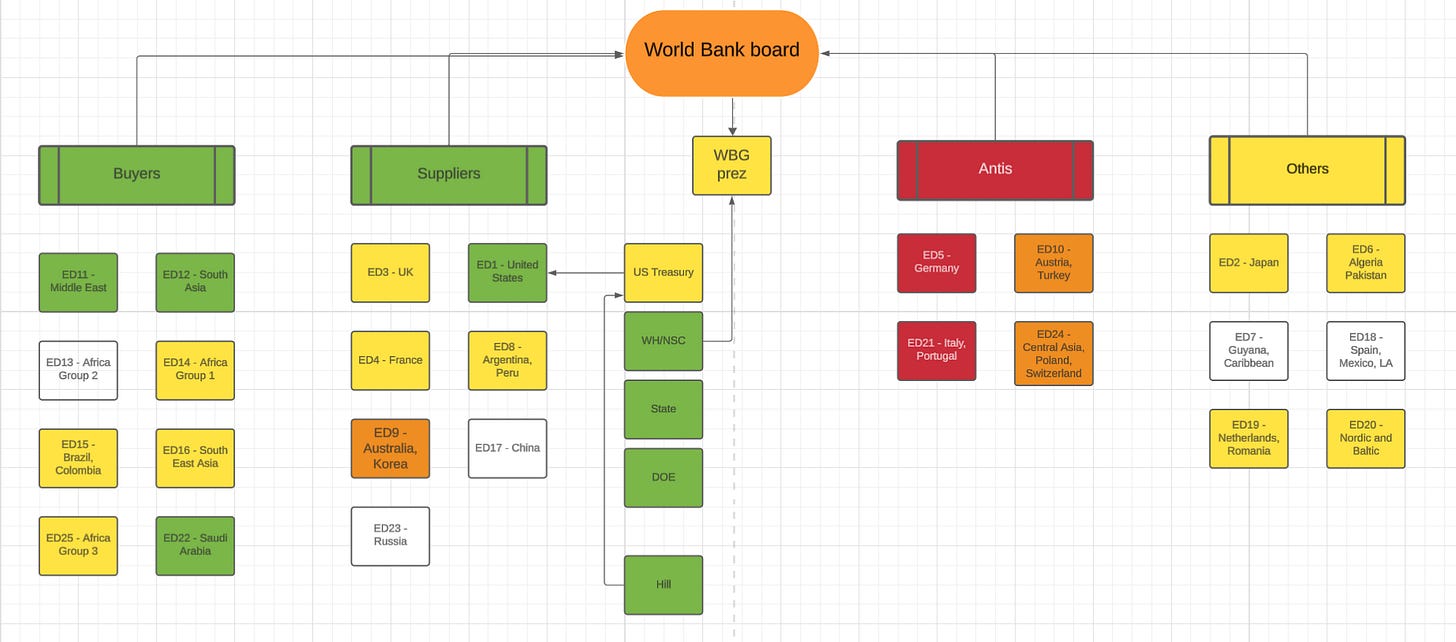

Understand the target. Broad appeals to do the right thing rarely work. It’s much better to understand the dynamics inside the institutions we’re trying to impact. The World Bank is not monolithic, so we approached it at multiple levels. For example, we parsed the board members into groups that would be supportive, ambivalent, and opponents of change. We crafted outreach to each board faction and looked for opportunities to pitch different messages to each. We appealed to the World Bank president (Malpass and then Banga) or people around him. We probed for allies among the World Bank staff too (yes, we found a few). And, perhaps most importantly, we prioritized the most influential shareholder of the Bank, the US – or, more specifically, the US Treasury which controls the US seat. Our approach included direct appeals to senior Treasury officials and indirect pressure via Congress, the White House, and other executive agencies. Legislation like the International Nuclear Financing Act didn’t even need to pass, it just had to attract bipartisan support to create the intended effect.

Understand your opponent. Who is going to block us? And how do we either flip, sideline, or bulldoze them? We learned exactly who inside the World Bank was opposed to the change and why. We opted to bide our time and, in the end, work around them.

Constantly re-assess. People change, views change, and opportunities arise. We started poking around on the nuclear ban way back in 2018. At the time, even talking about nuclear was sensitive at the Bank and almost all of the shareholders I spoke to thought it would be impossible. Yet, over time, shifts created new allies. Japan, for instance, went from anti to ambivalent to supportive. Changes in the nuclear market also helped, such as the agreements big tech companies signed with nuclear developers, which suddenly made people think again about what might be possible. We even created an internal color-coded schematic to track our gameplan over time. And when we learned that one big objection was no money for nuclear expertise inside the Bank, we pivoted to pitch a trust fund. New allies, new problems, new solutions.

5. BUILD alliances, both on the inside and outside.

We need both. On the inside, one example was working closely with DJ Nordquist, the US rep to the World Bank board during Trump 1 who was trying to quietly crack open the door by talking with other board members about nextgen designs. Once she left office, she became an even more vocal advocate for a new nuclear policy, and then, after the 2024 election, she was back in the White House. Several Hill staff were also keen to help push, so we worked with them on multiple fronts. On the outside, we strategized with ClearPath, the highly effective center-right clean energy group, and Third Way, the center-left think tank. And we collaborated with allies at the Breakthrough Institute, such as Vijaya Ramachandran who had her own networks inside the Bank. This inside-out, left-right coalition helped to create a bipartisan effort that could talk to all parts of the Bank, all factions of Capitol Hill, and make a variety of arguments to different audiences.

6. PERSIST

Patience is a virtue. From the first discussions with World Bankers and Hill staff to the policy change was more than seven years.

7. WAIT for your moment.

Windows of opportunity arise unpredictably. To finally lift the World Bank ban, we (arguably) needed a hard-charging anti-globalist president back in the White House. The Biden team was increasingly open to nuclear for climate reasons but generally hesitant to push the Bank too hard. The Trump admin doesn't care about emissions but they want the World Bank, if the US is going to stay a member, to be open to all energy technologies. They insisted the Bank pull its head out of the sand – and do it quick.

8. LEARN

We reflect on what went right, what went wrong, and what can be applied to future ideas. After-action learning makes think tanks smarter and more effective in the future. For me, the World Bank experience underscored that we should attack problems via multiple channels and we should always treat target organizations as dynamic and responsive to changing incentives. People are dynamic and responsive too.

A final thought on what we did not do.

No long report. No big conference. No fireside chat with John Kerry. We wrote emails, sent 50+ one-pagers, harangued Hill staff, bartered for intel, drafted talking points, took discreet coffees. In the final stages, we shifted to a public tack. I wrote several Subtack posts and opeds to aid with specific policy targeting. And, out of our usual style, we produced a short video to use with certain audiences to get over last minute wobbles.

We don’t have an exact recipe to copy for our next big idea. But we have eight clear steps to try to follow. And, I think, a pretty good story to tell.

Great little essay on how to get things done as a Think Tank. I, for one, appreciated your lack of long reports; whats's the need when the message is so simple?

Well done Todd and team for your part in making this change happen!

Thanks for writing this, Todd. It’s a model of think/do that I know, love, and have even deployed myself once in a while. It’s also a model that works in a certain political / policy environment, and I wonder if Washington still functions that way. I can say that from 3,000 miles away it sure doesn’t look like it.