Energy Access is not the same as Energy Abundance

What Maslow can teach us (and maybe M300 too) about the Hierarchy of Electricity Needs

A debate is raging right now inside the halls of powerful organizations over what counts as an electricity connection. The answer will decide what happens to billions of dollars and will affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Does a home lighting system count or not? Should we aim higher for more impact? Or aim lower to reach more people? Should energy investment be prioritized for households or for industry? What do people need to live better lives?

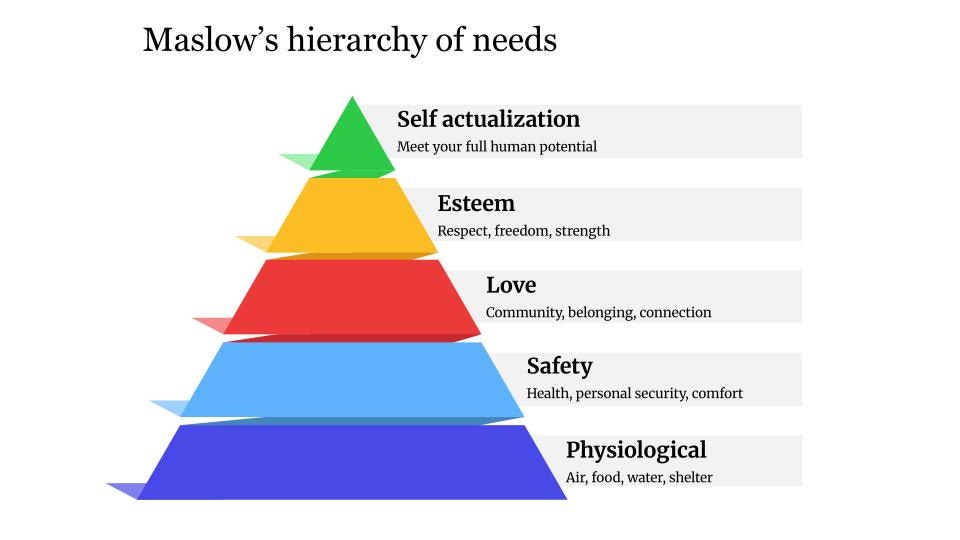

A recent chat with my son about harm reduction strategies for opioid use disorder turned to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and it got me thinking about (what else?) energy. Maslow’s pyramid is a powerful heuristic about how our brains work, what we desire, and how our needs evolve as we make progress. Ultimately, Maslow’s idea is about what it means to be human.

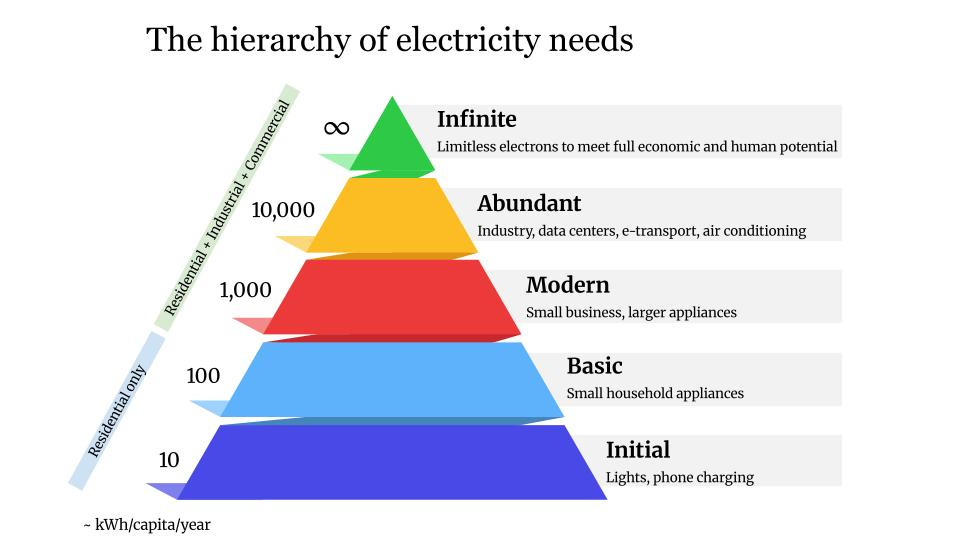

A similar pyramid could help us conceptualize our energy needs. So I made this up:

If you read Eat More Electrons, you’ll know I’ve long been frustrated by the binary notion of energy access. So frustrated that I started a whole organization dedicated to dispelling the idea that energy is about a simple connection.

The debate that’s roaring right now is over what counts toward meeting the 300 million connection target of Mission 300, a big new initiative from the World Bank and the African Development Bank. The end date is 2030, so time is tight and 300 million is a huge number. It’s entirely understandable that some want to keep the definition of a connection as low as possible so the most people can be reached. At the same time, others have legitimate worries that setting the bar too low will sell poor people short.

If an investment delivers very basic home systems that can power lights and charge a mobile phone but not much else, is that really in the spirit of energy for development?

Or, in a world of limited resources, if we set the bar too high, we’ll probably reach fewer people and maybe even overdeliver systems to people who aren’t yet rich enough to use more power.

Maslow can help us understand the debate – and maybe point to possible solutions.

Let’s get beyond the binary

I’m a fan of the World Bank’s multi-tier framework which proposes measuring household energy access in 5 steps along different dimensions. It’s a massive improvement over the binary access rate commonly used. I wish the World Bank would use these 5 tiers much more in its own operations and not just as a theoretical construct (more on this below).

My main gripe is that the top Tier 5 is not nearly high enough. I doubt many World Bank staff would be happy with up to 3 power outages per week or be able to live on 3,000 kWh per year. But 5 tiers is definitely better than one (tiny) one.

I’m an even bigger fan of the Modern Energy Minimum which, not coincidentally, I helped to create. It’s a new metric of 1,000 kWh per person per year. The real innovation here is not just that it’s higher than other thresholds, but that it covers both electricity at home and in the wider economy. The metric proposes an annual per capita minimum of 250 kWh for residential power (equivalent to the World Bank’s Tier 4) plus an average of 750 kWh used in commerce, industry, and agriculture. Tracking both is important because we generally use electricity at home to live better lives, while we use power at work to earn a better living.

People need both. If they have power at home but not at work, they’re usually too poor to afford much electricity or the appliances that use power. This is pretty much the reason we see small or nonexistent income impacts from initial household access. The real development bang from electrification comes from boosting business and livelihoods, not home appliances.

The emphasis on residential power is understandable. We all think about our refrigerator or holiday lights more than the invisible electricity of a faraway data center or the electrons embedded in the manufacturing of all the things we use every day. We even talk about a power plant serving X thousand homes. Yet only about one-quarter of the world's electricity is residential. This ratio explains the Modern Energy Minimum’s 250/750 split too.

Moving from energy access to energy abundance

As much as I think a 1,000 kWh target is a great idea, it’s still not high enough as an end goal. The Modern Energy Minimum is intended as a helpful second step after initial access. But we actually need to go much further if we want economies to transform and people to live full lives. My adapted version of Maslow’s pyramid might help us conceptualize how.

Maslow also has me thinking about Amartya Sen. His big idea was that development is not as much about material wealth as about having choices in life. The title of his seminal Development As Freedom pretty much says it all. Maslow would, I think, agree.

It’s human to need food. But it’s also human to then yearn for security, then freedom to make choices, and even to aspire for liberation to live a life how we choose.

Energy is the same. Start with lights and aim, eventually, for a life where infinite energy liberates us to live our best selves.

I hope the chart mostly explains itself, so I’ll stop here.

What Maslow might mean for the World Bank and M300

Connections are a great goal. Let’s make as many as we can and let’s hit the 300 million target. But let’s also aim to not just get people to the first level of an initial connection, but move them up the ladder/pyramid. Let’s track not just initial connections, but each step up. Let’s set goals for new and improved connections. Let’s count people moving from zero to Tier 1, but also from 1 to 2, and so on.

The old constraint to doing this was any ability to track electricity use. That is now solved. More details to come, but Stephen Lee has cracked that problem. We can now track electricity consumption at every level of the multi-tier framework – and beyond. I hope the World Bank and its partners adopt this new approach that’s consistent with the objectives of M300 and better aligned with broader development goals.

Most of all, countries need Energy for Growth

Obviously, the push for new and improved household connections cannot be at the cost of parallel investing in energy for business. That means building systems that are low cost and reliable. That’s what industry cares about. A Nigerian entrepreneur cannot possibly succeed paying $0.30/kWh while coping with constant outages against a Vietnamese competitor paying $0.07 for power that’s 99% reliable. If this persists, Vietnam will be creating jobs and livelihoods. Nigeria will not.

For M300 and others, this requires target metrics that are not about connections. They could instead aim for measurements of lower costs and better reliability. These have some data challenges, but they are surmountable with a little effort.

I sometimes hear arguments over whether connections should come first and industry later – or the reverse. Most success stories of energy leading to economic growth and poverty reduction (in the United States, Europe, or East Asia) have largely started with industry, allowed people to become richer, and then rural electrification was only later. It’s enticing to make that argument. Focus first on industry and the connection will flow later. I might believe this sequencing makes sense, but only in a technical vacuum.

In the real world, politics make that hard. People want lights now and politicians want to get re-elected. The revolution in offgrid solar – which many people incorrectly think I disfavor – means we don’t have to choose. This post by Nithio’s Kate Steel seems right to me. Focusing on initial connections does not need to come at the cost of building reliable cheap power for business. We can walk and chew gum, rather than fight about which comes first. But we must do both.

When we’re thinking about the energy needs of the world's poor, data tracking is no longer a barrier. The main thing holding us back now is our own ambition. And our own imagination of what’s possible.

Over 90% of countries in Africa are ruled by dictatorships of one form or another. The World Bank, IMF and UN have mandated "green" energy as a condition of billions of dollars of loans to these countries, for decades. By "green" I mean solar and wind. I am not certain what funds are set for these governments to build green facilities but know that virtually every power grid is useless and needs tens of billions to repair or replace, plus the planning and skilled workforce that is virtually impossible in Africa. This is the fundamental reason, that even China with its +20yr "Belt and Road" initiative, has failed to electrify one African country.

These recycled conversations are tiresome. I think it’s an absolute shame that we are still dealing with energy access issues in 2025. More babies/mothers die of energy access each year than during the COVID pandemic. Given the remarkable success in Pakistan it is clear the transition can lift all boats in all societies. Unfortunately despite Todd’s push for more diesel and fossil fuels hand outs, the world has more people without reliable electricity today then when Todd started making these arguments in 2010. Energy access is a solvable problem and we really need to aim higher. Technology is ready and cheap, now we need to figure out what is stifling commerce.