Africa’s energy transition is not British (or American or German)

The West can really only support Africa’s evolution to a high-energy low-carbon future by following the continent’s lead

Climate summit season is upon us. Next month is the Africa Climate Summit in Nairobi and soon after there will be another COP, this time in Dubai. A core unresolved issue: what rich countries are actually willing to do for poor countries. These — plus a recent invitation to give evidence to the UK’s All Party Parliamentary Group for Africa on British support for just energy transitions — all got me thinking about big picture guidance. What should rich nations do that would be good for the planet and also supportive of Africa’s future?

Everyone says they want Africa to grow and be part of the global economy and also fight climate change. Yet there’s a palpable sense from talking with African officials that it’s not working. The overwhelming message I am hearing from the continent: you talk about partnerships and we’re all in this crisis together, but you’re not behaving like that’s true. Instead we get lectures and are treated like second class global citizens.

I’ve written elsewhere about the racism in climate policy, the ways we get climate justice upside-down, and what we get wrong about energy poverty. But what is the positive advice for policymakers trying to do the right thing? Here’s a version of what I submitted to the UK parliamentary group.

The Big Issue: The Risks of Punching Down

We know the world needs to move to net zero emissions and that countries will transition at different speeds depending on their resources, capabilities, and other immediate needs. However, we also know that, in Africa, any policy that prioritizes near-term emissions reductions over economic development will deliver almost zero climate benefits, while potentially hindering poverty alleviation, job creation, and resilience to the effects of climate change. Such an outcome is literally the opposite of the goals of climate justice.

Essential Context: Low-emitting energy-poor countries in Africa face unique challenges.

Lots to say here, but any guidance has to start with at least a few basic facts:

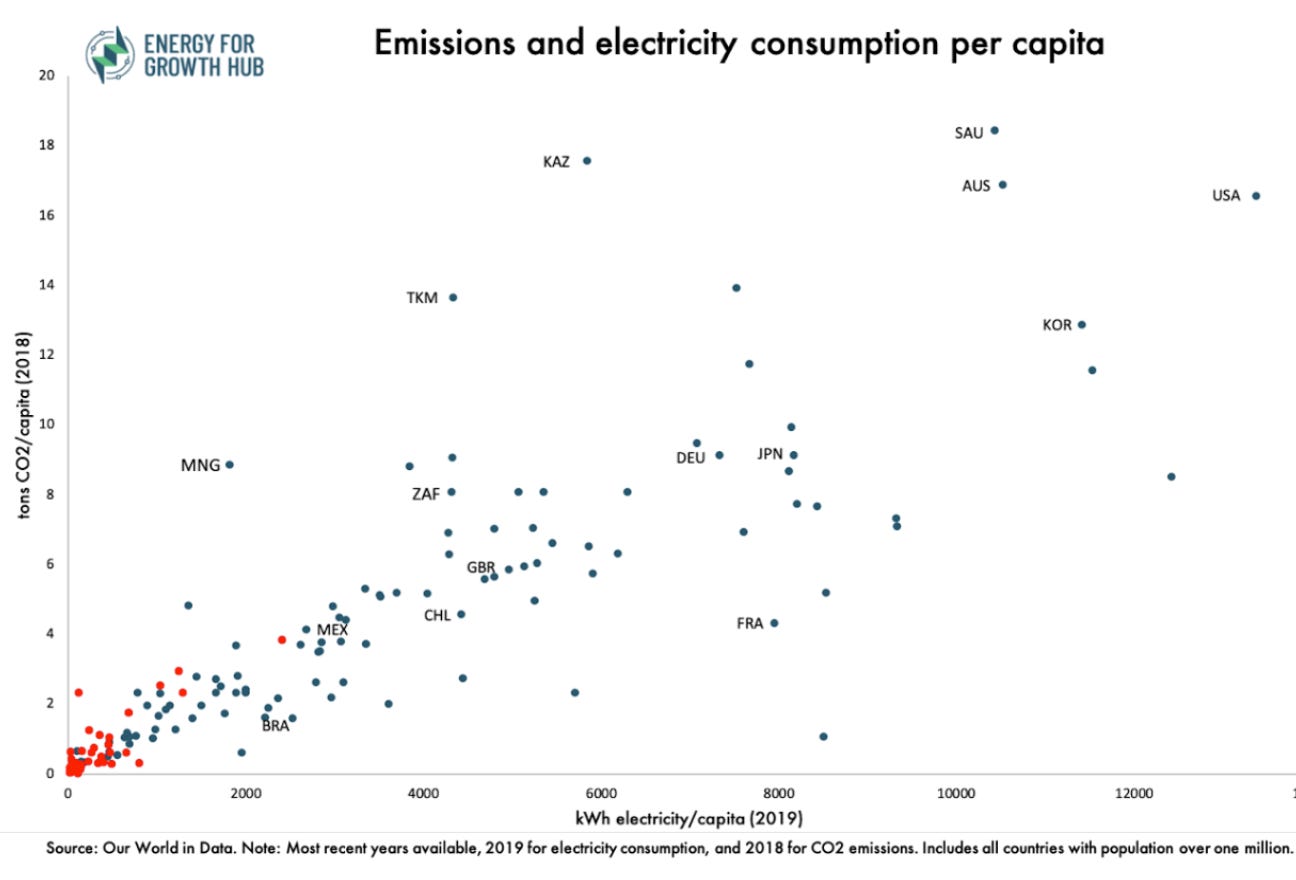

Energy poverty is chronic. Power, when available, is often too unreliable and expensive to enable job creation. Per capita consumption in many African countries is under 200 kWh per year (less than My Fridge), versus more than 4,800 kWh in the UK and 12,000 kWh in the United States.

Africa hardly emits any CO2. Sub-Saharan countries have contributed almost nothing to the cumulative emissions that cause climate change, just 0.6% of the global total (ex-South Africa). Even today, because they are energy-poor, African countries emit extremely low levels of CO2, about 1 tonne per person versus more than 5 tonnes in the UK or more than 14 tonnes in the US.

South Africa is a coal anomaly – and a poor proxy. South Africa alone accounts for 94% of sub-Saharan coal-fired power capacity and more than two-thirds of the region’s CO2 emissions. Its unique energy challenges are a horrible guide for the rest of the continent. (And please stop scaring people about a coal renaissance in Africa. It’s not happening.)

Africa’s energy transition is more about raising consumption than lowering emissions. In the rich world, the energy transition is about decarbonizing high-energy, high-emissions economies, while protecting jobs, industry, and high standards of living. In Africa, the energy transition is about expanding access, building energy systems to create jobs, industrializing, and enhancing climate resilience. Africa’s transition must prioritize development while setting the stage for a prosperous low-carbon future.

Figure: The Continent is Not the Problem (African countries in red)

Ok, enough throat-clearing already. What’s the guidance?

IM(not so H)O, the UK, US, and others could far more effectively support fair and just energy transitions in Africa by following six core principles that are easy to love: agency, diversity, ambition, resilience, innovation, and equity. [Note: These ideas are drawn heavily from past work with some wonderful colleagues including Mimi Alemayehou, Katie Auth, Murefu Barasa, Morgan Bazilian, Brad Handler, Uzo Iweala, Rose Mutiso, and Zainab Usman.]

Here’s the list and what it means for policymakers.

Agency: Follow Africa’s ambitions and priorities. External support has to flow from partner country objectives. Goals with any chance of credibility have to be set in Abuja or Lusaka, not London or Washington.

Diversity: Be flexible toward technology choices (just as the West is for itself). Kenya’s low-carbon pathway will not be the same in Nigeria, or Britain, or Germany. Rich countries are all giving themselves lots of near term flexibility (see Germany restarting coal plants, the US building more gas, etc) when necessary. But it’s obviously far easier to try to impose constraints on other poorer countries, such as the COP26 pledge to stop funding fossil fuels overseas. (Always easier to be a hawk when rules only apply to them, not to us.) Blanket bans are almost always bad policy. Instead, rich funders should follow the simple rule of supporting energy solutions that match local conditions and needs.

Ambition: Aim for far more than lights. One of my pet peeves is when people (or the UN) conflate a few lights with modern energy. Solar lanterns and other small off-grid systems can provide very basic electricity. For the extreme poor, it’s better than nothing and a boost onto the first rung of the energy ladder. But let’s not confuse this with energy for development. That’s why Western funders in Africa should aim to elevate all people to at least the Modern Energy Minimum of 1,000 kWh per person per year. (And, consistent with principle #1, the minimum was endorsed by African energy ministers.)

Resilience: Get serious about financing adaptation – including by investing far more in (what else?) energy. Even with the most optimistic progress against climate change, African countries will be highly vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. Adaptation will require investing far more in new agriculture, clean water, better infrastructure, and, above all, making people richer. Energy is absolutely vital. Many of the most necessary adaptation technologies – air conditioning, steel, cement, and desalination – are highly-energy intensive. That’s why investments in robust energy systems are also investments in climate adaptation.

Innovation: Creative market-building can drive clean technology. By innovation, I do not mean selling Stanford-designed gadgets or pleading for naive leapfrogging. Both are popular but neither are answers to Africa’s energy needs. By market building, I mean investing in enabling infrastructure (let’s make transmission lines sexy), downstream industries that create jobs and provide anchor customers for power (China does this in Africa, the West does not), and especially by setting norms that allow for competition. Britain in particular was a very successful champion of transparency for mining and oil that made a huge difference. What not do the same for transparent clean energy?

Equity: Treat the remaining carbon budget as a development budget. If we have a limited amount of acceptable new CO2 for the next several decades, the most ethical – and most efficient – allocation is to prioritize new emissions where they deliver the biggest development benefits. The simple unassailable truth is that the next ton of carbon does the same damage to the climate no matter where it comes from, but it would do far more good to humanity in Senegal than in Germany. The uncomfortable conclusion is that a true commitment to climate justice entails occasional support for carbon-intensive projects. The equity case is pretty strong for downstream gas projects in Africa when they displace dirtier fuels like charcoal, catalyze industrial development, or provide the best technical and financial option for balancing higher shares of intermittent solar & wind. To be fair, the US Treasury guidelines follow this exact logic, provided any new gas projects are part of a country’s long-term transition plans. I hope we’ll see this pragmatic approach adopted in practice.

The Bottom Line: Respect. We can be aggressive on climate policy and also prioritize our own energy security and economic futures. We should expect African partners to do exactly the same.

Great piece! I think the 5 principles are a great way to look at justice and fairness in energy transitions not only in Africa, but in every continent, country and city. I see the agency element as a crucial one that receives very limited attention in just transition speeches and even frameworks. Engaging and empowering communities is truly easier said than done...

Yes!

What do you think about the bookMoral Case for Fossil Fuels? Seems to be a similar argument.

Let's build gas power in Africa.