Why crypto is not like an aluminum smelter

What makes a good anchor to spur more energy investment

My last post Hype Go Up criticizing the energy use of ₿ mining generated a lot of reactions, especially from enthused crypto advocates. One of the more compelling counterpoints to my skepticism goes something like, “Crypto’s not perfect but it’s generating income and attracting new investment.” On-grid, crypto can turn excess power into revenues for struggling utilities. Off-grid, crypto can flip stand-alone systems into the profit column. In other words, crypto mining could stimulate new demand for energy which may attract more capital to build the long-term power systems that energy-hungry countries need. This all seems plausible… perhaps…. but only under certain conditions.

The Anchor ⚓ as the Hammer 🔨

Two things are almost always true:

Power investments need an anchor customer to catalyze the project; and

Anchors get special deals to compensate for their risk-taking.

Ghana’s power system today still relies on the Akosombo dam which was built in the early 1960s. The project was a central plank of President Kwame Nkrumah's ambitious plans for his country’s industrialization and, oh boy, was it BIG: Akosombo was the single biggest post-independence investment in Ghana; it created the largest man-made lake in the world; and, at around 900 MW at the time, it represented a 22x (!) increase in the new country’s electricity capacity.

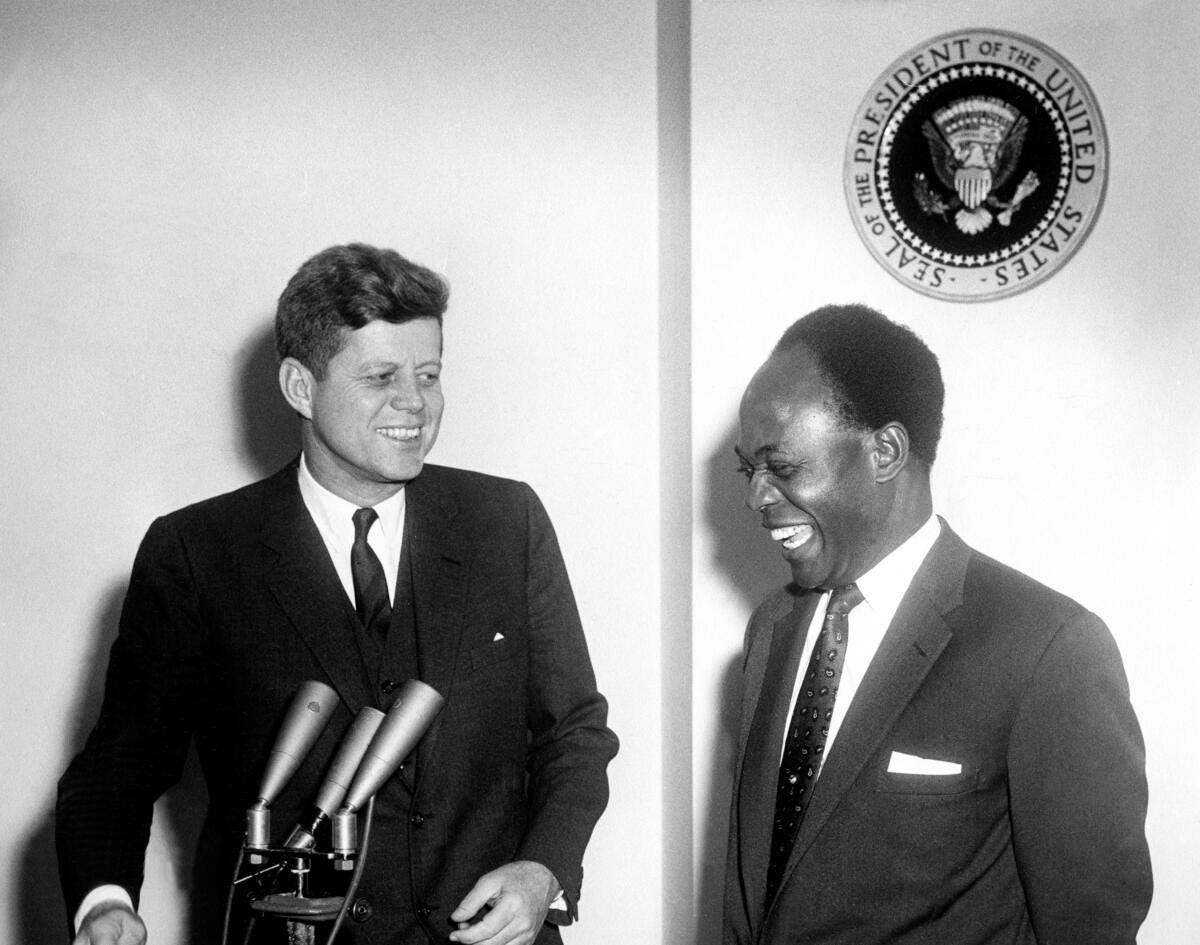

For the United States and Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy, the project was an attractive way to keep Ghana out of the Soviet orbit and promote the US capitalist model. (Any of this starting to sound familiar?) Because of its strategic importance, the dam was partly financed by the World Bank and the US Export-Import Bank. To make the project bankable, US aluminum giant Kaiser became the anchor customer. The Volta Aluminum Company (Valco) consumed the vast majority of Akosombo’s power at a cut rate plus generous tax exemptions while exporting most of its output. Nearly 60 years later, Valco is still running, although it was nationalized in 2008 and runs at only a fraction of its capacity because Ghana needs Akosombo’s juice for other things.

What does any of this have to do with crypto today? With hindsight, lots of hard questions remain about how Ghana could have better leveraged Akosombo for more industrial growth. At the same time, it’s hard to see how the country would have attracted investment at that scale to build essential infrastructure that, six decades later, still provides nearly one-fifth of its installed capacity. The argument I’m hearing today is that crypto could be like Kaiser by providing an income stream to make projects bankable and help to build the long-term infrastructure a country needs. That’s why we need to ask…

What makes a good anchor customer?

The starting point – which I can’t believe I need to make but I do – is that power generation is a means to an end, not an end itself. Creating demand for power and getting customers to pay for it is useful but only if:

Stimulating demand serves some greater purpose, like jobs or better living standards, and;

Benefits outweigh the opportunity costs or negative environmental impacts.

In other words, the short-term bankability of a project doesn’t matter one whit if the ultimate goal does not advance larger development or national aims. So… what makes a good anchor?

I think about this question across four dimensions.

1. Spillover: Does the power project create jobs?

This is arguably the most important factor for assessing an anchor customer for the simple reason that most governments prioritize job creation. For illustrative purposes, the best spillover outcome would be a new power plant that catalyzes a factory or other industry that creates lots of direct jobs and even more indirect jobs in the local community. At the other end of the spectrum is, well, power for crypto mining which creates zero jobs and has zero spillover benefits.

Mining for export or intermediate processing like aluminum smelting is somewhere in the middle as these activities create some direct jobs, but the local spillover depends greatly on the contract terms and the inclusion of local firms in the supply chain. In Ghana, for instance, Valco employed about 2,000 people at one point and helped create several local aluminum companies that used its output. But Akosombo never sparked industrialization anywhere near the scale Nkrumah envisioned.

2. Depletion: Is the power source draining a national resource?

This matters for the long-term sustainability of the economy and depends greatly on the technology. Solar power is effectively infinite, so there is no zero-sum loss to the country from exploiting solar radiation. At the other end is natural gas, which is absolutely a fixed resource and its use today creates a direct opportunity cost for tomorrow.

Geothermal and hydro depend on how the resource is managed. Geothermal, which is hugely promising because it is a firm (non-intermittent) zero carbon source is tricky. It’s theoretically infinite on a planetary scale, but each individual geothermal plant taps a specific reservoir that has a definite lifespan. In Kenya, for instance, some geothermal plants reinject steam to extend their life, but this is interrupted when the plant is used to balance (intermittent) wind which results in venting steam, which cuts the life of the reservoir. Exhausting geothermal for crypto mining would be a tragic waste in Kenya, but if crypto is only using otherwise curtailed power (and thus helping reduce venting), it could even be a net benefit for stabilizing the power system. Management of dams and geothermal reservoirs is hard to prejudge ahead of time, but secret contracting invites bad outcomes. Another reason for, ahem, contract transparency.

3. Income: How much money are we really talking about?

Countries need income and energy generation can provide it. That’s why countries export oil and gas. The same goes for solar via plans for green hydrogen exports. In fact, Ghana’s smelter is really just exporting cheap hydropower in the form of aluminum ingots.

In the power sector specifically, shoring up the finances of the national utility would be a huge benefit. Despite lots of promising new business models, no country is going to develop successfully without a national utility that can provide scale and reach. Not all people and industries need utilities, but all countries do. So a steady income stream from an anchor power customer can be a foundation for the utility to invest in maintenance and expansion for the national good. This is super important.

But the amounts matter too. If the anchor is paying near or below cost, it’s not really much of a net benefit. From the outside, of course, it can be impossible to know if the contract is truly beneficial to the utility or not. (Again, contract transparency!) But my next question suggests why not all income-generating anchors are the same.

4. Durability. How long will the anchor stay?

Power plants are inherently long-term infrastructure, so you need a reliable anchor in it for the long haul. When it's a mine, smelter, or factory, the investor is making a commitment to the country because they cannot easily just pack up and leave. Crypto is uber-mobile. The whole reason 21 crypto mining firms are moving into Ethiopia is because they fled China for cheaper and safer power elsewhere. But literally nothing is stopping them from packing up and leaving when another lower-cost power source arises.

Bankability is not the same as development

So, let’s not confuse ends and means of power investment. Arguing that crypto is wonderful because it makes your specific project profitable is not the same as saying it’s good for a country. Crypto mining may make sense if it is using solar (or flared gas or otherwise wasted power) and not competing with other more productive uses, now or in the future. A trickle of income may help individual projects or a utility at the margin. But otherwise it’s exporting for exports’ sake and not creating any local value. That’s not development. No country in its right mind would build its future economy on such a plan.

The bottom line: countries need anchor partners to build the power systems they need. But they must choose their anchors carefully.

This is a useful reminder that the universe is transactional. You are always exchanging some resource for another resource. The key to remember is to get the maximum viable resources in the exchange.

Very interesting history of the Volta dam. Thanks for sharing.

Ultimately the answer comes down to 3 things: do you think the invisible hands works better than the alternative, do you think Bitcoin is a better currency and even if you don't for either of the above then what would you have Ethiopia do?

Invisible Hand:

If ones idea of creating jobs is Africans doing back breaking work swinging a pick in a mine all day, clogging their lungs or in an aluminum factory, then yes, Bitcoin mining won't provide that. But I think both of us want high skilled jobs coming to Africa. The kind of IT techs that manage bitcoin mining rigs. And, here's where the invisible hand comes in, who knows what that could cause... New skills, new startups, Ethiopian govt learns to price their electric better, which creates better environment to build power generation for the indefinite time Bitcoin mining is there, Ethiopia generates more income they can save for a rainy day, which allows them to plan a few years ahead, etc. Nothing measurable. But that's how the invisible hand works.

Further, if there is under priced electricity in Ethiopia then the invisible hand should solve that. If, as you point out, the electric company is selling power below cost they should stop doing that. That's not an issue with Bitcoin. Bitcoin arbitrages energy prices. It would be very expensive to send Ethiopian electricity to China. But it's cheap to turn Ethiopian electricity into Bitcoin and send the Bitcoin to China. This saves a lot of infrastructure costs. Environmentalists should be jumping for joy for all the conservancies that don't have high voltage transmission lines going through them.

Bitcoin is better:

Is Bitcoin an improvement on Gold? And are other cryptocurrencies better than fiat currency? Not better in all respects but in many. Saying it's not better is like someone in 1899 saying horses are faster than cars and always will be.

Bitcoin costs money and energy yes, but dollars cost lives in war. It causes inflation. Proof of Work is a much preferable way to secure a currency than Proof of Violence (that the USD is worth something is because the US govt says it is and they'll shoot you if you try to make more of it or disagree with them).

Based on the comment in the last article that bitcoin is privacy focused, I surmise that you have a wonderful rabbit hole your inquisitive mind can go down to learn what Bitcoin actually is. I envy all the great insights ahead of you down that rabbit hole.

The alternative?

Let's say Ethiopia should discourage Bitcoin mining, what's your solution? Ban it? What kind of precedent does that set? How would it ever enforce that?

I'm 100% open to changing my mind if I hear compelling logic on one of the first two points + the third point.