What’s wrong with spending scarce development finance in rich countries?

Multiple mandates seem to be diluting DFC's core mission

When Ben Leo and I were first pitching the idea of a modern full-service US Development Finance Corporation (DFC) around Capitol Hill, we’d make the case that private investment was an underutilized tool. Driving capital to under-served markets would boost global development and serve US economic and foreign policy goals. The first objection was always about corporate welfare. Senators openly worried that a big new agency would get twisted by US companies to pad their profits. Our response was to show that, actually, the loans made by the existing agency OPIC usually went to small or medium-sized companies, with less than 8% going to Fortune 500 firms. So far so good.

The next objection was usually about market selection: what would stop the administration from just using DFC as an unaccountable slush fund rather than for development? Here, the answer was easy: Congress could direct the agency to prioritize poor countries. At the time, no one (including Ben and me) thought a hard income cap was a good idea as the future agency might need some flexibility to invest in slightly-richer emerging markets. That’s exactly what happened. The BUILD Act of 2018 that created DFC stipulated:

We thought this was a good sensible compromise that leaned on the scale for development but was still realistic about the occasional need to stretch the bounds of DFC’s mandate when it served a strong US national interest. It was also a bet that DFC (and its board) would exercise restraint.

What does DFC’s portfolio tell us about its core development mandate?

DFC finally opened its doors in 2020 and, three years later, we can see how it’s worked out. In an analysis with my colleague Hamna Tariq posted on the Energy for Growth Hub site, we find that:

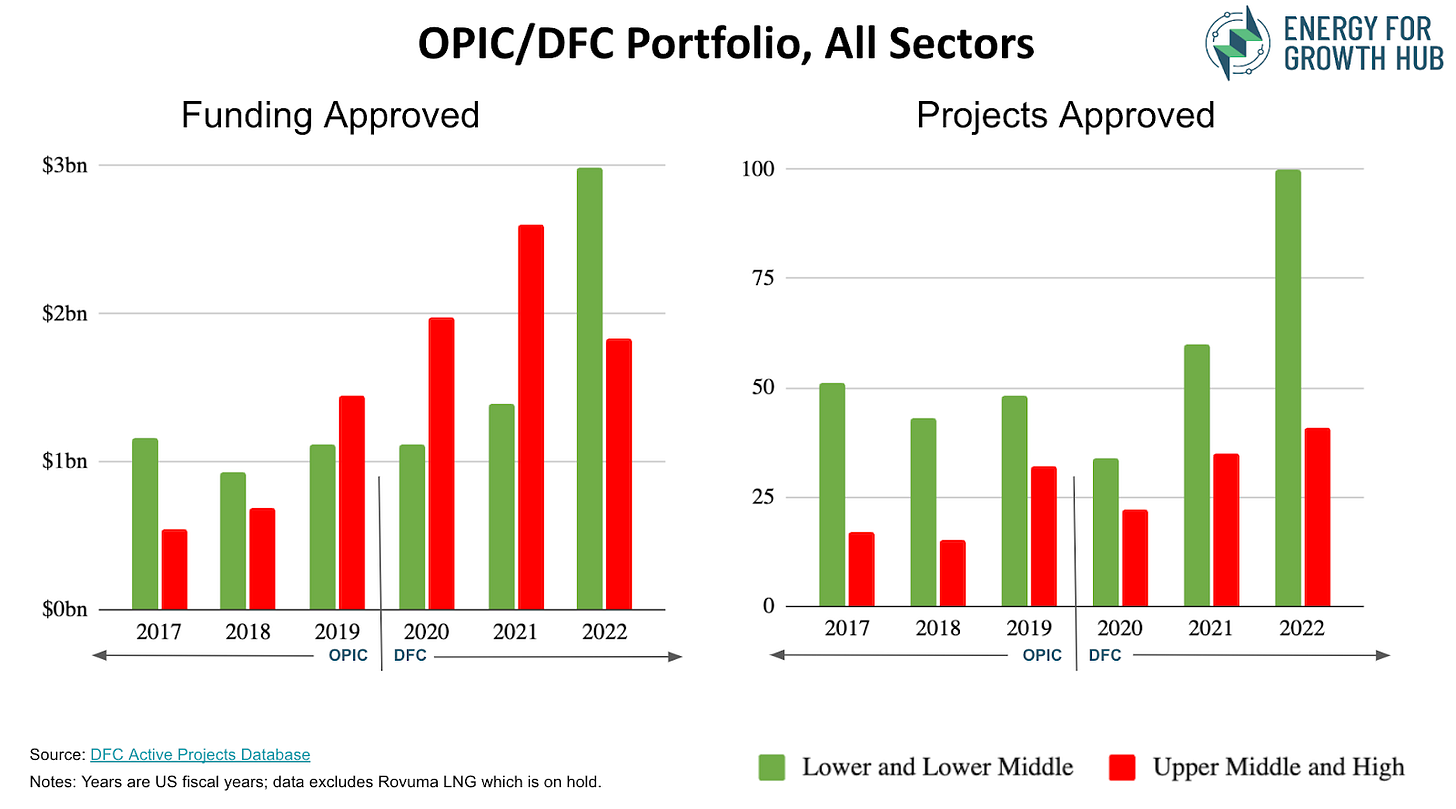

Hooray, DFC is doing a lot more than OPIC did, as measured by both financial commitments and project numbers.

Also good news that a majority of projects (66%) are in poorer nations, categorized as low- or lower middle-income by the World Bank.

But (wait a second!) a majority of dollars (54%) are now committed to richer markets, those classified as upper middle- or high-income.

Looking at the energy sector only, the balance looked a little better – until we include the most recent two quarters. Big new energy project approvals of $500m in Poland (high-income), $535m in South Africa (upper middle), and $144m in Ecuador (upper middle) skew the portfolio back to where even energy investment dollars are mostly going to richer markets.

Am I wrong to worry – or just naive?

Andy Herscowitz, until recently the DFC’s chief development officer, has a red hot response to our analysis where he basically says: if you care about development the right metric is project numbers not dollars. In fact, he thinks focusing on dollars out the door is a terrible idea because it would encourage the DFC to ignore small high-impact projects in poor countries (like business startups) and focus instead on large high-dollar value projects (like mining). Andy isn’t mistaken. Which is why we showed both projects and dollars.

But it still strikes me as deeply wrong that an agency set up for investing in poor countries is now devoting the majority of its resources to non-poor markets. The built-in flexibility was supposed to allow exceptional cases but those exceptions have become the rule, at least in dollar terms. That seems like a big problem. And IMO contrary to clear congressional intent.

How to be flexible while preventing mission drift

I’m not a development-only fundamentalist. I know that DFC can be a useful tool for tackling pockets of poverty in richer countries and for supporting US foreign policy aims. And it’s clear that congress has sent mixed signals too, for instance with the European Energy Security and Diversification Act, which specifically directs DFC to invest in countering Russian influence, regardless of country income level. (Hence Poland.) The administration wants to use DFC to fight climate change too which inevitably pushes the agency into richer countries (and raises hackles among Republicans). So DFC has been laden with multiple conflicting mandates and it’s trying to serve multiple masters. But it can go too far – and I’d draw the line at the majority of dollars going to non-priority countries.

I’m confident that each of the rich-country projects is defensible on its own merits. DFC has a highly professional staff and a robust process for vetting individual projects. But the risk is the accumulation of all those transactions skews the overall portfolio over time. That’s exactly what seems to have happened. Countering Russia in Europe, helping poor communities in Brazil, and funding marine conservation in Ecuador all push the portfolio up the income ladder – and further from its original mission.

Make it a little easier to invest in the poor – and little harder in the rich

Here are three ways to mitigate those risks – all ideas that could be done now at zero cost. I'll be pushing for each (and more) come DFC reauthorization, which is due by 2025.

Exception justifications should be public. Every project that isn’t in a poor country currently needs to get a waiver or be on a list of “safe harbor” sectors. That list is not yet public and obviously should be. The specific waiver criteria used to justify extraordinary impact or a national security interest is very far from clear. This lack of transparency invites abuse and skepticism.

Traffic lights! More clarity for decision makers and the public would help too. A simple approach is to color code each project by impact and income group with the entire portfolio reported publicly by share of each category. Ben Leo and I pitched a version of this idea years ago and I tried again in 2020. Something like it would have helped create positive incentives inside DFC and among its board.

Create internal incentives for more projects in poorer markets. More (and bigger) projects naturally come from more mature (and bigger) markets. A suite of options could help DFC to build its own pipeline of potential projects – and these can be tweaked to incentivize risk-taking in lower-income markets. Ahead of reauthorization we’ll be proposing more specific instruments, but one basic example includes early-stage project development funds with generosity of terms tied to income category.

If people have other ideas, I'm anxious to hear them. For now, I’m worried how I will answer those same old questions from Capitol Hill about DFC’s mission and the guardrails to keep it on course.