What might NuScale’s cancellation mean for Ghana and other nuclear aspirants?

Uh oh. But let’s take a deep breath.

The big news overnight: NuScale, a leading US developer of small modular reactors (SMRs), announced its signature project is canceled. Both the company and the Utah electricity co-op customer have pointed to rising costs, mainly for borrowing and steel.

A few thoughts on what this all means.

This is bad, obviously. NuScale was a pioneer and this project (to be built in Idaho for customers in Utah) was the demonstration everyone else was watching. It was the first SMR design to gain regulatory approval and was expected to receive the first construction green light. While this is a blow to US domestic nuclear hopes, especially SMRs that can be dropped in to replace coal plants, it’s also disheartening for Romania, Ghana, and other countries that had signed some kind of agreement with NuScale for potential future reactors. When the demo disappears, everyone will really need to understand why.

Critics will of course jump on this. The nuclear industry has slowly been rebuilding credibility after Fukushima and gaining support for the technology as a necessary weapon for decarbonization. After all, we’re going to need a *lot* more carbon-free energy in the future. But anti-nuclear campaigners have often claimed that, even if concerns like waste and safety can be managed, it will never be affordable. This news provides more ammo. Let’s see what happens with other projects.

FOAK is always costly. The analogy is imperfect, but the first iPhone cost Apple $150 million. The entire idea of SMRs is that they are modular and will eventually be able to use partial prefabrication to drive down costs via scale. But getting to scale means getting over the early humps. This first hump proved too much.

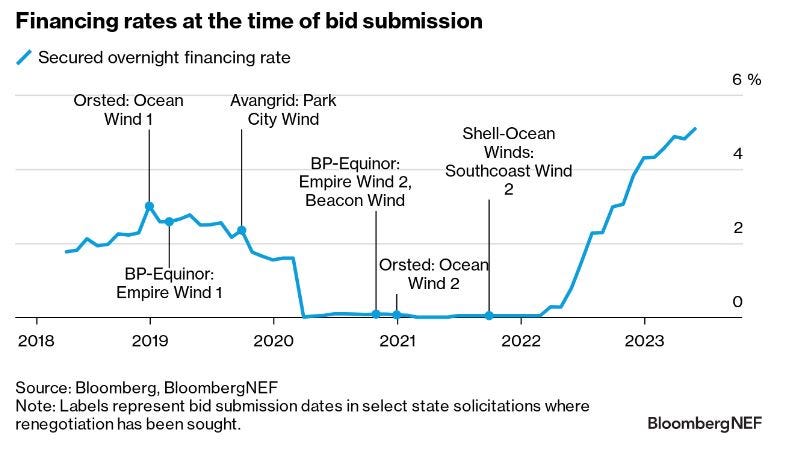

The ripple effects of higher US interest rates are laying waste to lots of industries – and other sources of clean energy. Nuclear is not alone. Every industry is affected by higher borrowing rates, but especially capital-intensive projects with higher upfront costs relative to running costs. What else is capital-intensive? Wind and solar. That’s a big reason a major offshore wind project in New Jersey was just canceled too. So this news is a worrying sign for all technologies that are dependent on patient low cost capital.

The likely (short-term) winner: natural gas. While the blow to nuclear power is no win for renewables, it will almost certainly help natural gas. Even with all the risks of volatile future gas prices, building gas-fired power plants is much cheaper upfront. So it’s relatively less affected by short-term interest rate movements. We’ll see what happens in Utah, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the canceled project is replaced with at least some new gas capacity. That will of course mean higher emissions. If you’re Ghana and your plan is to replace gas power with nuclear in about a decade, you might think about pushing that timeline further down the road.

Fortunately, a vibrant nuclear ecosystem exists. Let’s remember that NuScale is one startup. Oklo, X-energy, Terrapower, GE-Hitachi, Kairos, and dozens more companies are planning to bring new models to the market. The clean energy team at Third Way has been tracking more than 75 different advanced nuclear projects in North America alone, plus (working with my colleagues) at least 50 more globally. Many will fail, but I’ll bet not all of them. The neoliberal in me thinks this is exactly why government support should be, as much as possible, generalized for sectors rather than picking specific company winners.

Flexible nuclear power will still be attractive in some emerging markets. The price of electricity is far higher in many places where their options are more limited. A kilowatt-hour is roughly twice the price in the Philippines or Ghana than it is in Utah. The idea of modularity (the NuScale model for instance was a 6-pack of 77 MWe modules) is still compelling for fast-growing markets that need to deploy power at scale and in remote areas. NuScale’s problems might give countries pause, but I don’t think it will ultimately dampen demand, especially for industrial anchor customers.

Financing is still everything. The big issue ahead of COP28 is the cost of financing for infrastructure. Barbados PM Mia Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative is (rightly IMO) demanding cheaper money for poor countries. If we expect nuclear technology to play a major role in meeting global demand for clean energy, we’re going to have to drive down the cost of capital, especially for emerging markets. That will mean getting the US DFC more involved and, eventually, the multilaterals like the World Bank.

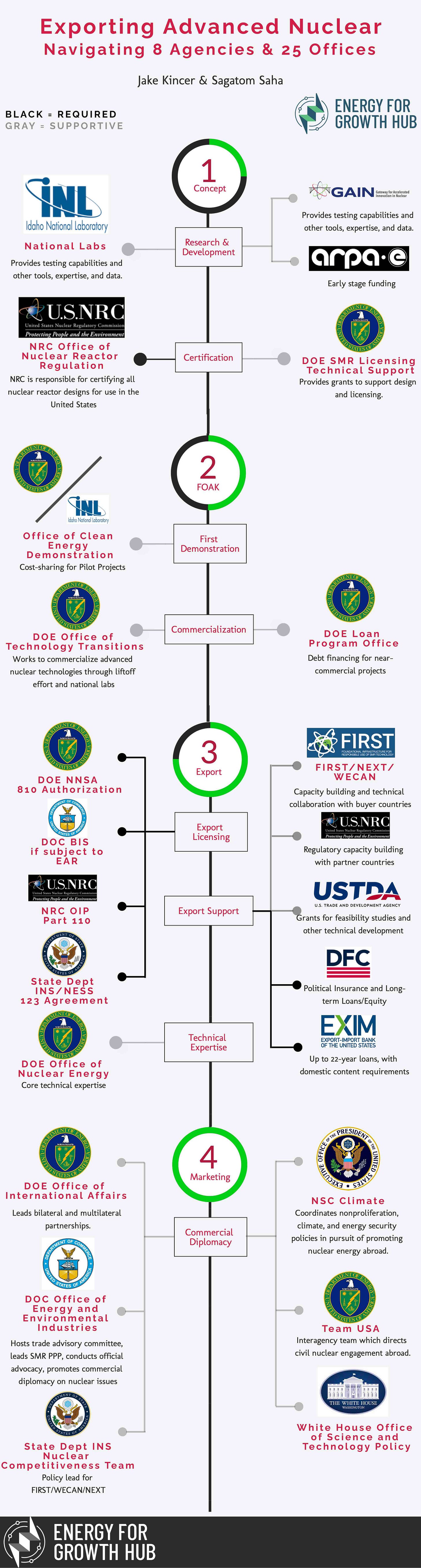

Closing thought on the urgent need for the USG to streamline.

The Biden Admin has aggressively supported nuclear technology. But if you’re one of these startups hoping to create a whole new industry to help save the world, you have to run a gauntlet of 25 offices across 8 federal agencies. We can do better. If we want nuclear tech to succeed, maybe we shouldn’t force companies to endure this 👇👇👇