My colleague Katie Auth recently told me that her favorite Substack posts are personal dives down a nerdy rabbit hole, so here goes.

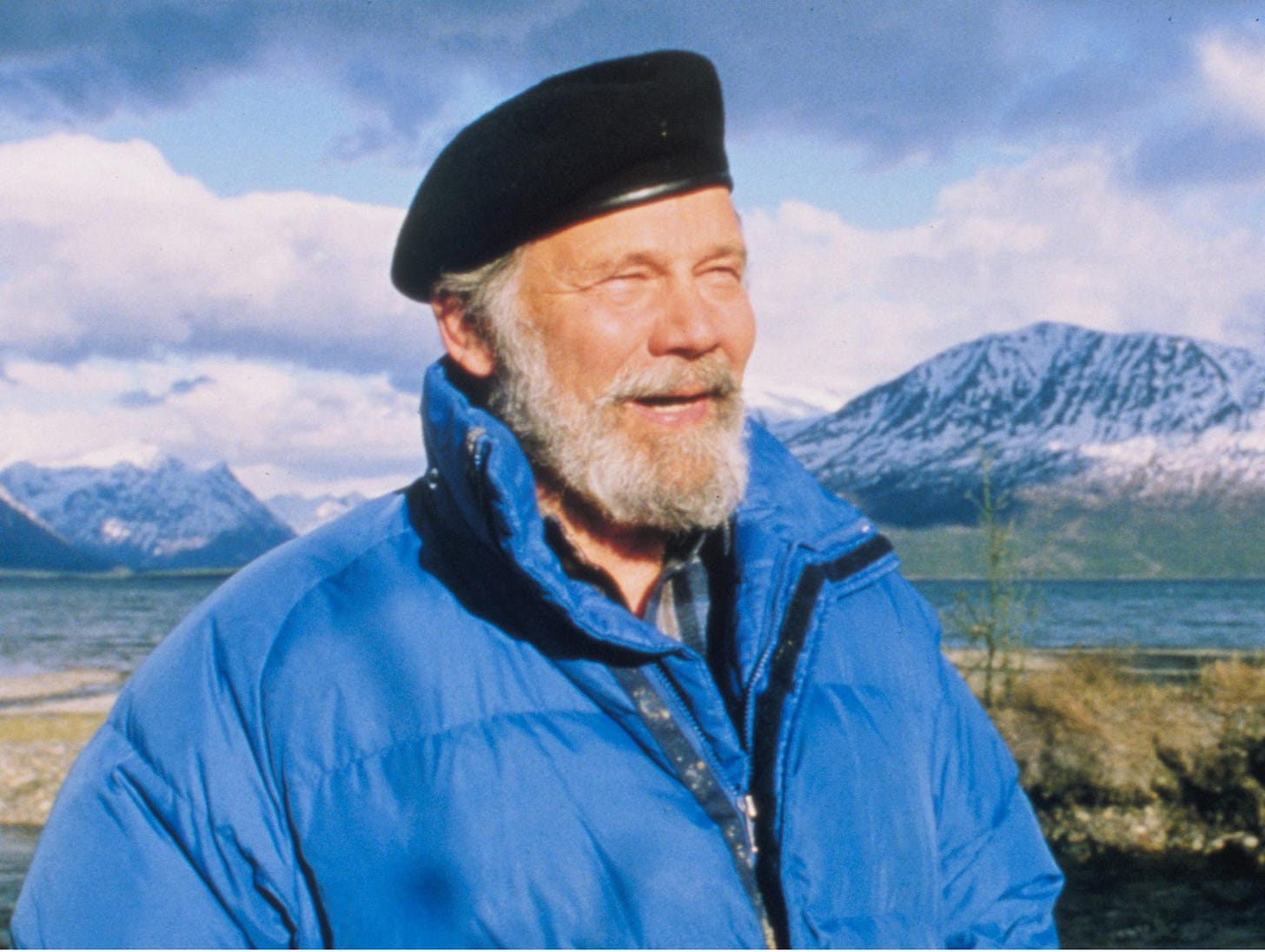

Jay Hammond is one of my heroes. I admire the former “Bush Rat Governor” of Alaska (1974-82) for many reasons, but most of all for being a policy pioneer. He was the main architect of the Permanent Fund Dividend which since 1982 has paid every Alaskan resident a share of the state’s oil profits. In 2024, the dividend was $1,702.

I’m thinking a lot about Governor Hammond again, especially with the election in… Suriname. Here’s why.

Why Governor Hammond was so special

I’m sad to say Jay Hammond died in 2005 and I never met the man. To be honest, I had only vaguely heard of him until I received a random email in 2011 from a Hammond family friend offering me a peek at an unfinished manuscript the former governor had been writing on how Alaska’s experience might hold lessons for Iraq. I was asked if I’d consider publishing it at the think tank where I worked. I was skeptical of course.

But once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down. Hammond was direct, laugh-out-loud funny, and refreshingly honest about his mistakes. I learned details of how his life experiences shaped his political views and the origins of his citizen-shareholder idea, which began in the tiny fishing villages of Bristol Bay and evolved to eventually become one of the great experiments in democratic governance. I loved it.

Hammond was no hippie dreaming of a socialist utopia. He was a hard-as-nails frontier Republican who thought that easy oil money made politicians lazy. So his innovation was to make people direct owners with regular dividends as a way to discipline politicians. Citizens would get a fair share plus they would be incentivized to pay attention to how their collective resources were being (mis)used. He saw the dividend as a vehicle to hold politicians accountable. As the sitting governor, he wanted to constrain himself and his successors from squandering Alaska’s oil wealth.

Hammond’s ideas were early precursors to the universal basic income movement and the wave of successful direct cash transfer programs in Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, and lots of other places. When the email arrived, I’d already been thinking about adapting these lessons to new oil producers in Africa to help them avoid the worst potential effects of winning the lottery.

Saving countries from their own oil

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, two of my mentors Nancy Birdsall and Arvind Subramanian had proposed Saving Iraq from Its Oil by distributing oil revenues directly to each citizen, mainly as a way to hold the country together. I found their arguments persuasive. Ghana had struck oil in 2007, so Lauren Young and I floated a similar direct cash distribution scheme to ensure that all Ghanaians benefited from the boom and not just a tiny elite.

At the time, I was frustrated by a lot of the advice to the newly-resource rich countries, which boiled down to “be like Norway” and “create strong institutions.” This was like telling insomniacs to get more sleep. True but not remotely helpful.

Norway had 150 years of democracy before striking oil. That’s one hell of a headstart. So what, in a practical nuts-and-bolts sense, could young democracies do when facing a tidal wave of sudden unearned cash?

Citizen dividends from a national windfall seemed like a very concrete way to build the incentives for stronger institutions and accountability.

Giving people a direct benefit was good in itself.

Igniting public interest in governance was even better.

And perhaps the best outcome: using the dividend to establish a fair broad-based tax system to help countries thrive after the resource was gone.

I had been working on a book on the whole big idea when the Hammond manuscript landed in my lap.

I agreed to edit Hammond’s text into the core chapter of an edited volume, The Governor’s Solution: How Alaska’s Oil Dividend Could Work in Iraq and Other Oil-Rich Countries. I penned an introduction, added Nancy and Arvind’s article, plus new chapters by Scott Goldsmith on Alaska and Johnny West on Iraq. In 2013, I launched the book at the University of Alaska in Anchorage. I met many of Hammond’s original larger-than-life allies from the dividend battles, experienced the magic of Halibut Cove, and had the honor of flying to a remote cabin on Lake Clark to meet the governor's widow Bella and give her a copy.

Oil to Cash as a Big Idea

After my Alaska adventure, I finished Oil to Cash: Fighting the Resource Curse through Cash Transfers with Stephanie Majerowicz and Caroline Lambert, where we made the broader case for a citizen dividend along with design suggestions for specific countries. Although any payout would (of course) have to be tailored to each country’s context, we proposed a basic three-step model:

Create a transparent fund to receive revenues

Pay a regular universal dividend to all citizens using a simple public formula

Claw some portion back in taxes to establish a fair long-term tax system

We thought the economic case for Oil to Cash was strongest for Venezuela while the political case most compelling for Liberia. We also posited that new technologies in biometric ID and mobile money could keep costs low and make the entire system fully transparent and traceable. (And once a country built a national ID system and linked everyone to a digital bank account, they could not only pay dividends and collect taxes, but also have a ready-made pipeline for responding to disasters, targeting social payments to women or the poor, or replacing subsidies with cash.)

If you are already thinking of all the reasons this idea can’t possibly work, I encourage you to please skim Chapter 6 “Oil-to-Cash Won’t Work Here! Answers to Ten Common Objections” before you email me or post a comment :)

Both books were published by the Center for Global Development and, for my favorite Eat More Electrons readers, are downloadable here for free: The Governor's Solution and Oil to Cash.

Okay, but is it happening?

I enjoy writing books. But books are just not a great way to make policy change happen. It takes a lot of talking to people, learning, and adapting. Making policy ideas a reality also takes patience and luck.

We have seen some green shoots of progress.

In Liberia, a smart young aide to President Sirleaf helped insert cash transfers as an option into its oil law. But promising early offshore exploration didn’t pan out so a Liberian oil boom never arrived.

A version in Iraq was seriously considered by the US-led Coalition Provisional Authority — and, I was told, later by Shia Sadrists — but ultimately never tried. (Apparently, neither Paul Bremer nor Muqtada al-Sadr wanted to constrain themselves.)

Mongolia attempted a version of sharing mining revenues, but the politicians overdid it and had to dial the program back.

Bolivia is a close example where the government uses gas revenues to fund its national pension (i.e., cash transfers for retirees).

But no country has yet fully embraced the full Oil to Cash concept.

Suriname could be the first?

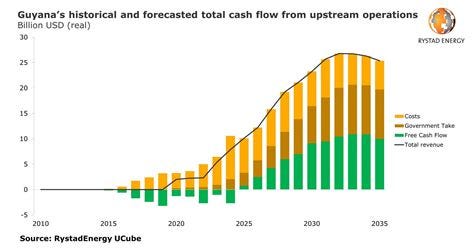

Suriname is a South American country of about 600,000 people on the cusp of a massive resource boom. Last year its leader promised "Royalties for Everyone.” President Chan Santokhi explained, “every Surinamese who lives in our country receives a savings note worth US$750 with an annual interest of 7 percent. The money will be paid out in the future from the royalty income” from oil and gas starting in 2028.

Sure, the idea is a gambit to win votes. In parliamentary elections held just last Sunday, the parties of Santokhi and his chief rival Jennifer Geerlings-Simons are nearly tied, so the next president will be chosen in coming weeks by a complicated negotiation in parliament. I have no idea how it will turn out. But how to share the oil spoils is at stake.

If Suriname follows through on Royalties for All, it would give people a tangible stake in national wealth and bind the government closer to its citizens. If designed well, the plan should generate direct benefits for regular people and incentivize them to pay attention to how their government negotiates with oil companies and manages future income. It might even constrain politicians from their own worst instincts.

The stakes are higher than just one small country. Suriname’s neighbor Guyana might be next to experiment with direct dividends. I hope they try it. Lots of other countries are watching too.

Jay Hammond would approve.

Great post, Todd! As you know, I very strongly supported your proposal of cash transfers from oil revenues in my book From Dutch Disease to Energy Transition, published in 2023, freely available on ciep.energy

Fingers crossed that Suriname and/or Guyana will adopt this in practice in the near future!

So honored I can take (partial) credit for this one... loved it!!